Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. | sitemap

Bladder cancer typically refers to cancer that starts in the urothelial cells that line the bladder. The bladder is a hollow muscular organ in your lower abdomen that stores urine.

It is the most common type of cancer in the urinary tract. The predominant type of bladder cancer is transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). While not as common, TCC can also occur in the kidneys, pelvis, ureters or urethra as these structures are also lined by the same urothelial cells that line the bladder.

There are other types of bladder cancers that are rare:

This article will be focusing on TCC.

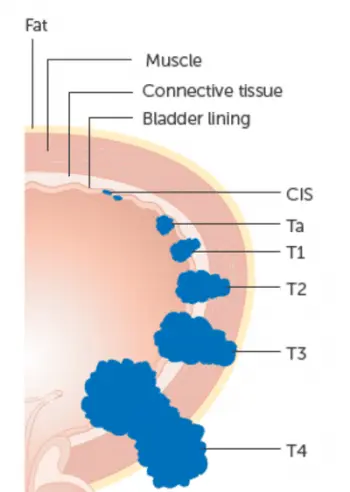

Bladder cancer is classified into non-muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive types based on the depth of invasion from the innermost lining towards the outer layers of the bladder. Approximately 70% of newly diagnosed urothelial bladder cancers are classified as non-muscle invasive.

The stage of urothelial bladder cancer is determined by the depth of tumour invasion into the bladder muscle and outer layers, spread into nearby lymph nodes and spread to distant sites.

Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer Tis, Ta and T1 tumours are classified as non-muscle-invasive bladder cancers.

Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer Bladder cancers that have penetrated into the muscular layer of the bladder wall are termed muscle-invasive bladder cancers (T2, T3, T4).

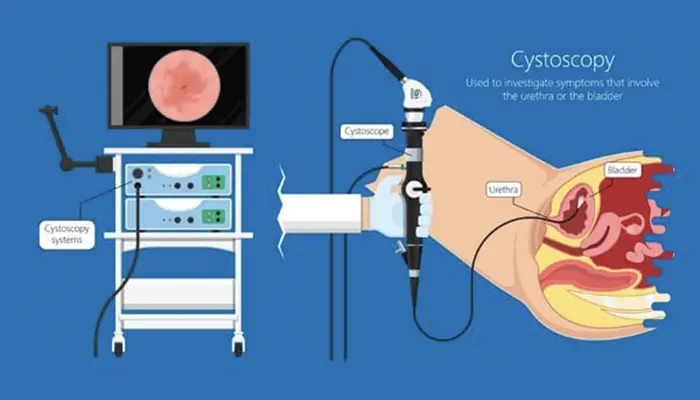

Once muscle-invasive bladder cancer is diagnosed from cystoscopy, imaging studies are used to further define the extent of local invasion, involvement of adjacent lymph nodes and distant spread.

Computer tomography (CT) is cross-sectional imaging routinely performed to obtain this information. CT urogram captures images of the kidneys, ureters and bladder and CT of the chest will exclude distant spread to lungs and lymph nodes in the chest.

Occasionally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) urogram is performed when a more detailed visualisation of the extent of direct growth of cancer into the bladder wall and adjacent structures is desired.

Bone scans may also be considered for the detection of bone spread. PET scan is sensitive for the distant spread of bladder cancer but is not very helpful for assessment of the local extent of bladder cancer as the tracer used for this scan is excreted in the urine.

Occasionally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) urogram is performed when a more detailed visualisation of the extent of direct growth of cancer into the bladder wall and adjacent structures is desired.

Bone scans may also be considered for the detection of bone spread. PET scan is sensitive for the distant spread of bladder cancer but is not very helpful for assessment of the local extent of bladder cancer as the tracer used for this scan is excreted in the urine.

Transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT) followed by a single dose of post-resection instillation of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) in the bladder (intravesical BCG) is the main treatment for superficial (non-muscle invasive) bladder cancers. Sometimes, a second, more extensive TURBT is done to better ensure that all cancer has been removed.

For patients with a high risk of recurrence based on stage, grade, number and size of cancers, a longer course of intravesical BCG is recommended after the surgery. Strict adherence to careful surveillance protocol is important as patients remain at risk of recurrence and progression to muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Those with recurrent non-muscle invasive bladder cancers may need repeated TURBT with intravesical BCG or surgery (radical cystectomy); depending on the stage, grade and duration since the last dose of intravesical BCG.

Anti PD1/PD-L1 immunotherapy is currently being explored as an alternative to radical cystectomy in BCG-unresponsive non-invasive bladder.

Surgery is the standard of care for BCG-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancers and muscle invasive bladder cancers. Radical cystectomy is an operation where the whole bladder and adjacent lymph nodes with prostate (men) or uterus, fallopian tubes and ovaries (women) are removed.

After the bladder is removed, reconstructive surgery is done to allow urine to be stored and drained out. Usually, draining ureters from the kidneys are connected to a refashioned short segment of the intestine that acts as a urine pouch. One end of the refashioned urine pouch is connected to the abdomen skin where urine can flow out.

Radical cystectomy is a major surgery and not all patients will want to do it or are medically fit for it. Bladder preservation strategy using a combination of TURBT followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy is an alternative in a minority of patients.

Most patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancers will be recommended to have neoadjuvant chemotherapy (chemotherapy prior to surgery). Administration of cisplatin-containing combination chemotherapy prior to surgery reduces recurrence and improves survival in muscle invasive bladder cancers. Kidney function needs to be preserved for the safe use of cisplatin. Patients with swollen kidney(s) from bladder cancer compressing on ureter(s) will need to have the obstruction relieved. Following surgery, further adjuvant treatment with Nivolumab (anti PD1 immunotherapy) improves disease-free survival by 30% for patients with high-risk muscle-invasive bladder cancer, based on CHECKMATE 274 study.

The first line of treatment for metastatic bladder cancer remains combination chemotherapy containing cisplatin in patients who are suitable to receive cisplatin.

For cisplatin-ineligible patients, anti PD1/PDL1 immunotherapy is an alternative in patients with tumours that are positive for PD-L1 expression. The role of anti PD1/PDL1 immunotherapy has also been defined in maintenance treatment after initial cisplatin-containing chemotherapy and in patients who have progressed after cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

On top of immunotherapy, additional promising progress in the treatment of metastatic bladder cancer has been made in the form of targeted therapies. These treatments work by blocking specific proteins/mutations found in cancer cells. Fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFR) inhibitor, Erdafitinib, has shown activity in patients who progressed after chemotherapy and have FGFR2 or FGFR3 mutations identified in the tumour. Enfortumab vedotin is an antibody that targets cell adhesion molecule nectin-4 commonly found on the cell surface of bladder cancers. The ideal sequence and combination of drugs for metastatic bladder cancer is actively being explored in clinical trials.

In a nutshell, TCC is the most common type of bladder cancer and is often associated with cigarette smoking. Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer is managed by local resection (TURBT). High-risk cases will benefit from a course of BCG administered into the bladder. For muscle-invasive bladder cancer, management typically involves the administration of cisplatin-based chemotherapy prior to definitive surgery to remove the whole bladder.

In a carefully selected group of patients, a bladder-preserving approach may be appropriate using a combination of TURBT, chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy remains the cornerstone treatment for metastatic TCC. However, new drug discoveries in the form of immunotherapy and targeted therapy have greatly expanded the treatment armamentarium for this disease.

The Cancer Centre @ Paragon

290 Orchard Road #17-05/06

Paragon Medical (Lobby F)

Singapore 238859

The Cancer Centre @ Mount Elizabeth Orchard

3 Mount Elizabeth #12-11

Mount Elizabeth Medical Centre

Singapore 228510

(by appointment only)

The Cancer Centre @ Mount Elizabeth Novena

38 Irrawaddy Road #07-41

Mount Elizabeth Novena Specialist Centre

Singapore 329563

BOOK AN APPOINTMENT

Incorporated in 2005, Singapore Medical Group (SMG) is a healthcare organisation with a network of private specialist providers across four established pillars - Aesthetics, Diagnostic Imaging & Screening, Oncology and Women's and Children's Health. Within Singapore, SMG has more than 40 clinics strategically located in central Singapore and heartland estates. Beyond Singapore, SMG also has an established presence in Indonesia, Vietnam and Australia. Learn about our privacy policy here.